|

Story titles on this page : The Well of Blood. Toilet Requisites. The Feud.

Our Uncle Bert.

Its a Cows Life.

Christmas.

THE WELL OF BLOOD

My earliest recollection of life was my home high in the Welsh mountains. To me it had so many advantages living well off the beaten track. There was no need to wash every day because no one saw you, clean or dirty. At the final count there were ten of us up there, but I am jumping ahead now. Dad wanted sons to follow him. He struck lucky on his first attempt and was extremely lucky to have another son on his final run - with six daughters in between.

Riches! Well I suppose we had plenty but money was not one of them. My father was working in the local pit to subsidise the farm. The privilege of living on top of the world had to be paid for somehow. The old farm house had no electicity or running water. School was a case of hit and miss, with many more misses than hits because there were more important things to do than school, to my way of thinking anyhow. If it rained you got soaked long before you got to the classroom. If it snowed, well, there were snowmen to be made and foot print pictures to do and making a huge snowball and watching it roll down the mountain getting bigger and bigger as it rolled down, finally crashing.

The spring and summer were wonderful for us. In the spring, bird's nesting and daisy chain making. We would play for hours shining a celandine under each others chins to see if we liked butter. The summer brought the haymaking. That was work and we were all expected to do our share, so now you can see why school was not so important to us.

Our house was stone built with a steep track cut into the side of the mountain leading up to it. The house had a steep sloping roof with a sky light window set in it and it nestled in a natural dip, sheltered on one side by a steep bank that climbed almost to the roof. Three rooms up and three down and if you climbed up the bank, which we named the tump, you could see the top of the mountain, rolling on for ever, covered in ferns and yellow gorse. During the summer months its beauty abounded, but in winter it adorned a different gown. A cold barren one, covered in snow. It defied you to come to close

unless, of course, you were a fool. After years of growing up there I considered the mountain my friend. I knew all its nicks and cracks.

When my dad bought his "Paradise" he failed to take notice of a working quarry, no more than a few yards from our boundary. It was Penlan quarry where the famous blue stone

was quarried. Our first introduction to this was very early in the morning when a very loud whistle would be blown followed by the loudest bang we had ever heard. Then we were bombarded by UFO's, large and small, as stones became airborne, some landing in the yard, even on our roof. Mostly pebble sized but the odd one could be big and would smash through wherever it landed. This would go on at least twice a day for the next sixteen years. You put your life in your hands at those times. My mum used to say to my dad, 'now Bill, you can undertand why this place was empty all those years.'

This was generally the time my father would explode as well. Heading for the quarry he would rant and rave, but never did he achieve any thing. It did make him feel better though to have made his stand. Poor dad, with mum reminding him the promise of six months had passed six years back. After all the hard work he must have felt sometimes that he was battling the devil, but he struggled on day after day.

TOILET REQUISITES

One disadvantage to our life was our toilet, fifty yards up the garden. It was a little outhouse with a seat over a bucket affair.

In the winter, just as it was getting dark, my father would say, 'Anyone want the toilet, they had better go now before its dark as I'm not going up there later with anyone.'

We would be sat in the kitchen around about 8pm when the feeling of wanting the loo caught up with me. As quietly as I could I'd say 'I want the toilet.' This was the time my father turned into action man. Looking at my mother he'd say 'Brenda, I'm sure she does this on purpose,' and pulling on his wellingtons, rolling up a piece of newspaper like an Olympic torch, he would position himself outside the back door to watch and wait as I galloped up the garden, the Olympic flame burning brightly, hoping I could run faster than it burnt, kick the toilet door before you went in - in case the house guests were there - rats. Clamber up on the seat. Business done, there was little newspaper squares hanging behind the door and tripping trying to pull your knickers up as you ran, you was out of there as fast as you could and back to the warmth and safety of the kitchen.

THE FEUD

The nearest farm to us on the mountain was a couple of miles across the

top. It was owned by a middle-aged couple who had never had children

and, quite frankly, had no idea how to deal with them. They never mixed

with anyone either, if it could be avoided.

Our contact with them was very limited and if we did see one of them, it was generally the wife making her way home from chapel, or the village shop. She was always dressed

entirely in black. Looking back I can never remember seeing her in any

other colour, but I do remember she had a funny walk, short little steps.

If by some chance she had to pass us children she'd go right to the

edge of the track so she would not have any contact with us.Passing us like we had leprosy, and talking to herself, saying 'Oh dear, dear, dear, dear.' She soon became known to us as Mrs Dear, dear. We could not understand her one little bit, but dad make sure we were never rude to her. He would not allow that. Although he had a lot of friction with her husband, my dad always doffed his cap to her. I once asked dad why do you do that when Mrs Dear, dear passes and he said it was respect, love, respect.

Her husband was a very different kettle of fish. My dad said he was a belligerant old bastard, but not in my mum's hearing. Dad used to meet up with him as he travelled up and down the mountain. The belligerant old bastard would be riding an old farm horse, milk jack tied either side of the horse, to carry drinking water home to his farm. Wearing a long black coat, leather leggings and old trilby hat, underneath which was a red weatherbeaten face. He had blue steely eyes that could look right through you. With a whip in his hand he resembled Lee Marvin in "Paint your Wagon."

My mum said he was a typical hell-fire and brimstone type. We noticed he also

talked to himself, quoting passages from the bible to his horse, who must have known

them off by heart. We children would wait until he was past us before we would shout

names out at him. Our favourite was, "Hello Mr. Dewy Nose." We did not understand him and he made it very clear he neither understood or liked us.

They did all their own farming and you very often saw her ploughing. Looking back, she must have worked very hard but if we children so much as put one foot on their land, he would come running at us cracking his whip. It was a very good job we were fast on our feet, as he would have landed quite a blow if he had managed to catch us.

Dad and him never got on in all the years we lived up there. I remember the day some of our sheep strayed on to his land. Whe my dad went to get them back he ran at dad with a pitch fork, sending my dad home, with his pride, if not shattered, dented. My father was always saying, ' that man is not stable. I'll give him a wallop one of these days. He will drive me too far.' My mother, always the peacemaker, told dad just to ignore him because if he did hit him he would be the one in trouble because he was so much stronger than him. She was building dad up so that he did not feel he had to prove

anything to the world. When dad was out of earshot, mum would mutter that sod is

much heavier than dad and with that whip he could cut your father to shreds. Until then I had never realised my mum was clever.

Then came an afternoon when dad rushed in all excited, saying to my mother 'I've got him Brenda, I've got the old bugger at last.' My mum wondered what dad was up to. She did not have long to wait. 'The boyo up top,' dad said, 'his bull just walked down our track like he was a full time boarder. Do not let the children open the loose box door, I've got his bull penned up there.' Mum said, 'don't talk daft Bill, let his bull go.' Father was adamant that the bull stayed exactly where it was and he would lie in wait for the boyo from the other farm to come and repossess it.

It was late that night and all us children were in bed and supposedly asleep, when the belligerant old bastard came creeping down the track to our yard. It was a typical spying mission. Find the whereabouts of one bull. Dad lay in wait and all us children lay in bed, one ear listening for the fireworks to start. We did not have to wait long. All hell broke loose. Dad was now on his land and fully in control. 'So you have come sneaking on to my farm you dangerous old bastard,' shouted dad and fists up started to jump and dance around his intended victim. Windows flew up as us kids hung out of them . Ringside seats were not plentiful. I hoisted myself out through the skylight. I had a prime seat up on the roof. Through the light coming out of the kitchen door, two ghostly figures danced around our yard. Not one blow was landed but arms flailing, there were some near misses, that is until my mum came out. Without raising her voice she said, 'you'. she turned to the belligerant one, 'you get out of here and take that old bull with you now.'

The bull then made his appearance, travelling at a pace that he had not used since his

hay days. With dad ten feet behind him the belligerant one joined in the mad rush for

freedom as mum looked up at us children and said, just as quietly, 'you lot, back into

your beds, the show is over.'

Poor dad took him a few days to win mum round again. To be truthful he could not see where he had gone wrong. He had been the chief protector of his family. Although he promised mum he would curb his temper regarding the belligerant one,

Continuation of The Fued........

Well, there is so much more I can write about this period in my father's life, and in our nearest neighbour's life.

The episode of the bull was just one of many such incidents over the 16years we lived up there. None more exciting than the Court Case, yes, I said the Court Case!.

Our neighbour, if you could call him that, was taking my father to Magistrates Court over stealing a section of grazing that in the neighbour's eyes belonged to him, and dad was adamant it belonged to him and had planted quick growing hedge cuttings to steal his beliefs that the land was his, only to find several days later, they had been pulled up. This went on for months, shouting, swearing, hedge planting, until the day of the Court appearance, when, my dad, dressed in his best bib and tucker was off to prove his point.

After 20 minutes in the Court the Magistrates didn't know if they were on horse back or moon walking, as the ranting went to and fro. Neither my father or our neighbour had legal representation, and not only were they tying each other up in knots, they were driving the gentlemen on the bench crazy.

My mother always laughed after, when she reminded my father of the moment when the gentlemen on the bench told my father he was his own worst enemy. Poor dad, he was gutted when the land was awarded to our neighbour, but, as mother hastened to point out after, it was only a couple of feet across and no more than fifty yards long. Why all the fuss over it?, she didn't know, and so full of gorse and rocks it was fit for nothing, but my father came back to "the principle of it", one of dads favourite sayings.

Over the years it did very little to improve relations between the two. My father used to wish the earth would open up and and swallow that old devil, and i'm sure the neighbour was just as generous in his wishes for the demise of my dad.

OUR UNCLE BERT

I've told you about my Auntie Beat, dad's sister. She was four foot nothing of pure dynamite but she thought the world of my Dad, and would always be up and down the farm, lending a hand whenever needed. She was my mum's midwife when the babies were born and they were being born at an alarming rate too.

On the one occasion when my mother was due, Auntie Beat was on standby and had brought her husband, our Uncle Bert, up with her to stay for a few days. Now Uncle Bert was as knowledgeable on farming as my dad was on dancing, which means no knowledge at all.

I well remember when my Uncle decided to try out milking and sat under wrong side of the cow. He came flying out the cowshed door, bucket going one way, him the other, as the old cow gave him a good kick. Us kids thought it so funny and would all curl up laughing at his attempts. We would also slyly watch him do a detour around the old gander, because as soon as the gander spotted Uncle Bert, he'd give him a run for his money. But I'll give Uncle Bert full marks for trying. He'd not give up and would attempt many tasks.

Muck spreading was one job I can remember him trying his hand at. Of course, poor Uncle had little idea on how to go about it. It was a wild windy day when he took the horse and cart, full of cow manure, into the field to start. Now one thing to remember is don't try muck spreading unless the wind is blowing away from you. After the first half hour there was more muck over our Uncle than ever hit the field. He was covered in it and stank to high heaven. Dad said, ' stay down wind from me Bert' and my Auntie Beat and my mum would laugh their heads off at his sorry plight.

We did not have the luxury of a bathroom, so Auntie put a bucket of water on top of the fire to warm through for him to scrub down. 'And don't you come in till you have,' she shouted at him, 'you will stink the house out'. Us kids took the mickey out of him but he was a kind man and did not have a nasty bone in him. He towered over Auntie but she was the boss. What she said went. It was so funny to see her telling him off, half his size and he taking it all without saying a word. Yes, Uncle Bert's visit was as good as comedy any day of the week.

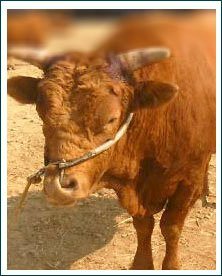

ITS A COWS' LIFE

My bedroom was situated over the cowshed which housed eleven cows. Through the gaps in the floorboards you could see into it, also you could smell it. This I did not mind, what's a pong between friends, and I considered the cows all my friends.

In the long winter months, when the cows never left the shed, the heat from their bodies would rise up and become my central heating. Their munching or chewing the cud and the occasional bellow was my background music and the smell was my perfume.

Cows are very interesting animals. They have the most beautiful eyes and in all the years on the farm I never saw my dad hit one. He would talk to them for hours and that is how I became a good talker to cows and it used to pay off. If one was calving and she was having trouble, a soothing word and a gentle rub of her tummy worked wonders. Lots of times calves come out front feet first. Tiny little hooves appear and dad would often tie a rope around them as they appeared and give a gentle tug, thus helping the cow pass the rest of the calf. I used to love watching them give birth. See the love between calf and mother.

Generally a cow's life is a sad, hard one. I am pleased to say all the cows on our farm had a good life and were all well looked after.

CHRISTMAS

It seemed all our Christmases were good. We did not get a lot of presents, but we ate well and we made our own fun. Mum generally made her puddings about three weeks before Christmas and, as she mixed the ingredients in a huge bowl, we all sat around the table waiting for our turn to stir the mixture and our one chance to make a wish. Mum put a few threepenny pieces into the puddings. They were silver and used every year. If we found one in our slice of pudding, we exchanged it for copper pennies and threepence was a great sum to go shopping with. The smell of the puddings, even before cooking, was lovely. Mum put the mixture into a basin, covered the top with greaseproof paper, tied them in an old pillow case and put them to boil in the old copper boiler for several hours.

Dad always killed a pig at this time of the year. Mum hated the thought of the pig being killed and would shut all doors and put the radio on full blast so she could not hear the squawking of the victim. Once the deed was done, mum would be out there to help dad prepare the meat for Christmas. First the pig would be hung up by its back legs to drain the blood out if it, then a couple of bales of old straw would be put down in the yard and the pig laid in the straw to be set alight. This was to burn all the hair off the pig. This done, its skin would be scrubbed clean until it was pink and spotless. Now the messy work began, with dad cleaning the inside of the pig and cutting it up, while mum salted all the joints to preserve them. She also made fantastic faggots from the offal and even today I can still smell the wonderful aroma of those faggots coming out of the oven. They were delicious. I have never tasted better since.

Christmas Eve morning, we would be up early as mum said many hands make light work and we all had a share to do. Dad would catch a couple of chickens, that were running in the yard, and wring their necks. Us children were given the task of the plucking them. Soon we were covered in feathers which we threw around at each other. The birds were now naked and ready for the cleaning, which was my mum's job. She was quick and thorough at doing it and soon the chickens were trussed ready for the oven. She stuffed them with home made onion stuffing which, when cooked, was beautiful.

Towards the evening we would all raid dad's sock drawer, looking for his biggest socks to hang up ready for Father Christmas to call. Hanging them along the wooden mantle shelf, with our names written on little labels, we went to bed as good as gold and could hardly wait for the morning.

Christmas morning dawned very early for us. As soon as it was daylight we would be up, rushing downstairs, to see if Father Christmas had been. There was mine and it was full.

My heart racing, I'd grab my stocking and dive back upstairs into my parents bedroom. Going to my dad's side of the bed I would nudge him until he reached out and pulled me up onto the bed. I would crawl in, still hanging on to my stocking and savour the moment of being in bed with my mum and dad. Every year they would say this is not coming off next year. But I knew I would be back.

Everything in the stocking was wrapped in layers of newspaper. I would generally get an orange, apple, a handful of nuts, pencils, drawing books etc. Nothing big like today's kids have. It was so exciting pulling it all out of dad's sock. Soon the bed was covered in old paper, nut shells and orange peel, but that never bothered me. It could not have bothered my parents either, they had nodded off again. Snuggling down, by the side of my dad, I would soon be asleep and that to me was Christmas morning.

The next highlight of the day was Christmas dinner and the pudding after, just hoping you would be lucky and get a threepenny bit. Dad would cut a holly tree out of the hedge and tied to it, amongst all the coloured paper balls, was a ten shilling note for each of us. This was to go into the bank. The joy of holding onto all that money, even if it was only just for a day or two, was something else.

I well remember asking my parents if I could have coloured soaps in my stocking one year, as we all used Puritan soap. Big rough cut blocks of it. 'Why do you want coloured soap?' my father asked. 'Because I want to grow up beautiful,' I said. Taking my hand he led me outside the back door, where a rambling rose was clinging to life up the wall. 'Do you see that rose?' my father asked, 'well that is beautiful and do you know what makes it so lovely? Once a week I put a bucket of cow manure around its roots, that is the secret.'

Do you know I walked through gallons of the stuff before I realised he was telling me porkies.

|